Saturday, January 10, 2015, I was to be in Paris for the day to meet poet and translator Marilyn Hacker. I had many questions about her experience with the ghazal and ghazal poets; she was generous enough to offer her day to me. On Monday 5th I booked my tickets to travel by the Thalys by Wednesday the 7th – Paris was not the same. Two hostage crises bolted through the city.

I stuck to my decision to travel. On the Friday – 9th – a day before my travel my friend asked me, “Why are you putting your family through this, traveling to Paris now?” I wanted to calm her fears. But I don’t think I was able to. I just could not think of anywhere I would have rather been than in Paris. That somehow the terror, fear, the tendency to self-preserve would not, and could not hold me back. Indeed I could have rescheduled but I did not want to. I wanted to meet Marilyn. I also wanted to see Paris, like when you approach your friend to hold her hand, to let her know she will be okay when things go wrong, not just in the summer when the air is crisp and flowers are in bloom, but in winter when it’s cold and the body struggles to stay warm. The combination of these two interwove to help me make my decision.

It was an unusually gray and stormy day. The Thalys had delays while the wind waged its battle I prepared my questions. Within me was this surging tide to go forth, to ask, to inquire, while this emotion presented itself there was also this ‘manthan’ (inner churn) – poetry in the midst of turmoil. Agha Shahid Ali toyed with the takallhus Shahid – witness and beloved. Marilyn had written that her name was not as meta as Shahid’s, when the jokes on Marilyn came out she left the room. Kashmir. Palestine. Poetry. Paris.

Online I read articles on the cities of the world and the need of the hour being introspection. Why indeed is the second generation of migrants turning elsewhere to answer their religious and cultural quandaries? Have the countries they were born and brought up not nurturing? Or had they been brain washed? Was there another kind of schooling that created the other kind – this kind – what kind? There is no straight forward answer. God needs protecting. Caustic, sarcasm, dripping ink in pen, then blood, lots of blood, blood everywhere on the pages, on tables, the floor, oozing from wounds, the American ghazal – of Adrienne Rich, Sharon Olds, Aimee Nehukumatahil talk of wounds, of hurt, Rich even says the way in which we murder is not the same anymore. Who is the gazelle today? Who the hunted, who the prey, who the hunter, who the almighty, Agha Shahid Ali “By Exile” wrote exiled by exiles, is this what is left of us? Birds fly over the landscape — Mahmoud Darwesh had asked where do birds fly after the last sky? Where do they go from here? And who are they? What hurts their heart? And what sort of God needs protection that too from creatures as fragile and faulty as us humans?

Bambi was sleeping on my bed when I left. He had kicked the duvet off, it half-covered his thin frame. His mouth was open. I could see his chest heaving steadily. His eyes twitched just a little. Was he dreaming? Would he ask for me when he woke up? Or would the iPad and Skylanders distract him enough for him to forget me just that bit – his forgetting me would hurt me. Ostriker had written in her essays in The Mother / Child Papers (1980) about birth and war time, the poignancy of the words raise a lump to my throat and I swallow it back with bad train coffee. The last time I was in Paris I was pregnant with Bambi.

—-

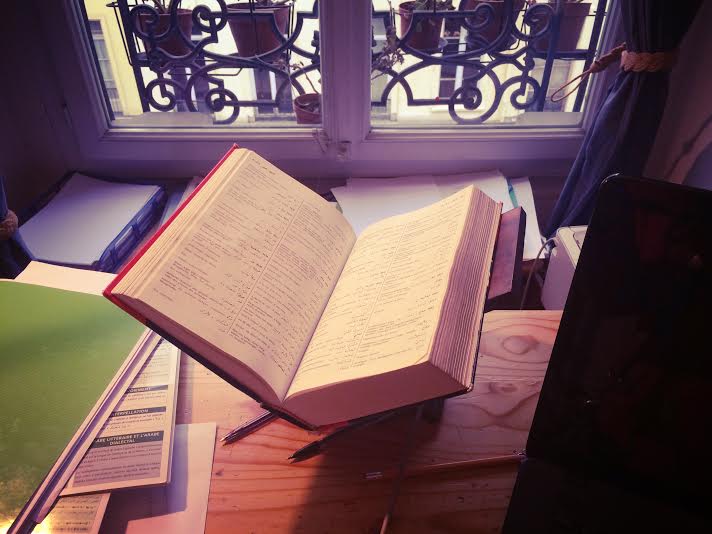

A long-winding dark bent wooden staircase curled up three floors to her small door; Marilyn opened it with a warm and gentle smile. Her office-living areas were covered in books. On the prayer stand open was the Arab to French dictionary, we both look at it, I tease her, “Is this what you have been worshipping Marilyn, have you done your hundred Bismillahs?” She laughs, “Oh yes I’ve been praying to irregular verbs.” She makes me coffee upstairs in her kitchenette with a Lebanese flag, over buttery croissants and raisin rolls we discuss ghazals. Her mind is sharp, wise, knowledgeable, a polyglot; she switches from Rumi, to Darwesh, to Ghalib, to Mimi Khalvati with such ease and grace. Somewhere my own ideas stretched, some modified, and some get fortified. While I start to understand Shahid better, women and the ghazal remain deliciously complicated. As a researcher one tends to be clinical about the work we study, for the artist it is more organic, natural, and inexplicable. She talks about her inclination towards anonymity, the idea to remain unknown – nameless, her last poetry collection was called Names (2010), she does not use the takallhus sometimes she alludes to it but most of the time she drops it. She says she enjoys doing that. It is fun to work with forms, to see how it functions, how far you can go with it, how much will it stretch. The ghazal becomes play-doh in my head and I start imagining what color it would be. I ask her how she knew about the ghazal, it was through Adrienne Rich, and Shahid, about Shahid she says, “He was very loved.” I can imagine that Shahid in his living room surrounded by his friends reciting poetry while the fragrance of a good rogan josh wafts from the kitchen. We discuss the differing styles of Shahid and Roger Sedarat. We analyze what it means for me an Indian living in Amsterdam to come to Paris to talk about an Arabic but more Persian-Urdu poetic form with an American-Jewish female poet, we notice the irony of it, also noting of how people and forms travel.

Marilyn takes me out for lunch to her neighborhood café. Where we meander away from the ghazal to nation states, and borders, and Paris, her reason to live in Paris was that she kept coming back to it and one day she decided to stay, she liked it there, her life, the book stores, the ability to have several literary options at her doorstep and the fact that she had studied French Literature in her youth. We talk of Beirut and our experiences with the city. She talks about Mosul and Syria.

I leave her apartment at five. She gives me her new collection of poems – with new ghazals – A Stranger’s Mirror (2015) – it is not yet in the stores, and she insists that I would understand it. I accept it. She gives me another book for Bambi. It is The Honey Hunter (2013) by Karthika Nair and Joëlle Jolivet; it is set in the Sunderbans, close to where I was born. I think of Bambi, and home, Marilyn smiles at me like she knows what I am thinking.

I go to the North Bank and walk along with the Seine towards Notre Dame across the bridge of locks, it is teeming with people professing their love, kissing, locking their locks, I pray for the bridge to hang on to its knobs and not collapse under the weight of too-much metal. The Seine looks angry. The sky is dark gray. The gothic elements of the cathedral look menacing. Every store, each corner has signs for Charlie. The air is somber.

I arrive at the station early. The taxi driver from Notre Dame to Gare du Nord tells me that on Sunday the 11th there will be a big demonstration to show solidarity and unity for Charlie. He says it is important to show it – that through this demonstration people want to stand together for Paris. He grew up reading Charlie’s newspaper and he could not believe what happened in the last two days, he says he has lost his ability to react, “Charlie was always poking fun at everyone, even himself, and I grew up reading his pages, this is my Paris, these are people from my childhood.”

It is pouring. The rain – “Even the Rain” (thank you Rafiq Kathwari for a poem I carry with me everywhere) – I am soaking wet. The Gare du Nord station is cold. There is police and military everywhere. I have to sit there and wait. Gare du Nord is no waiting room. But I have Hanif Kureishi’s The Buddha of Suburbia (1990) for company. There is a lover’s tiff in the station, it gets physical, the military officers step in, it is like a dance, the officers don’t really do anything, but they watch, they don’t say anything, they observe other people watching the couple, the couple, the officers movements are orchestrated, slow and mindful in comparison to the fighting fish who seem random – jerky – slowly as the couple moves away, the officers move as well, their faces are expressionless.

The train back to Amsterdam has police doing checks – they are still looking for the girl my co-passenger informs me, she also points out — good thing you do not look like her despite your dark hair. I nod, not saying anything; I try to make my face expressionless. I don’t think I am good at this. For the rest of the journey I remain buried in Kureishi. By the time I reach home – it is the middle of the night, stillness, Bambi is in bed, Purab’s waiting. The day drains away in the shower, steam, quiet, words forming, Seine curling, qafiyas, radifs, buttresses and mornings. They always come. Like the radif. Somehow even when the sun does not shine, the day starts, life moves.

—

Leave a comment