I have been ruminating on this topic for so long. It is time to stop reading it solely through the lens of an academic researcher and simply release it into the world, because its urgency can no longer wait.

This essay examines the influence of Persian poetry on American literature, tracing its path from transcendentalist appropriations to contemporary invocations of Rumi and Indo-Persian forms. Integrating recent scholarship on translatability and mysticism (Jabbari, 2016), it situates these intercultural flows within the geopolitical tensions of Orientalism and war, arguing for an ethics of reading that acknowledges both aesthetic resonance and historical violence. Concluding with a reflection on the significance of poetry and the humanities today, it calls for renewed institutional and societal commitment to research and artistic practice as forms of radical hospitality in an age of dehumanising metrics and global crisis.

The story of American literature is often told as an autochthonous emergence from colonial British letters, expanding into diverse vernacular and diasporic formations. Yet beneath this narrative lies a subterranean river of influence flowing from Persian poetic traditions into American verse, shaping its metaphors, spiritual vocabulary, and forms of address. Here, I explore how Persian poetry, with its mystical gardens, ecstatic metaphors, and devotion to an ineffable beyond, nourished American literature, offering not merely ornamental borrowings but a transformation of poetic ontology itself.

Emerson and the Birth of Transcendentalist Cosmopolitanism

Ralph Waldo Emerson’s 1846 Translations from Hafiz marked a decisive moment in this reception. Emerson declared Hafiz “a poet for poets,” admiring his ability to dwell in rapture while critiquing hypocrisy (Emerson, 1846). Fatemeh Keshavarz (2012) observes that Emerson’s encounter with Hafiz and Sa’di, mediated through German and English translations, catalysed a transcendentalist aesthetics rooted in an ideal of universal spirit and beauty. For Emerson, Persian poetry provided a model of thought in which beauty, wisdom, and divinity were inseparable. This influence was not mere textual borrowing but a reshaping of American poetic diction toward aphoristic wisdom, moral cosmopolitanism, and mystical union.

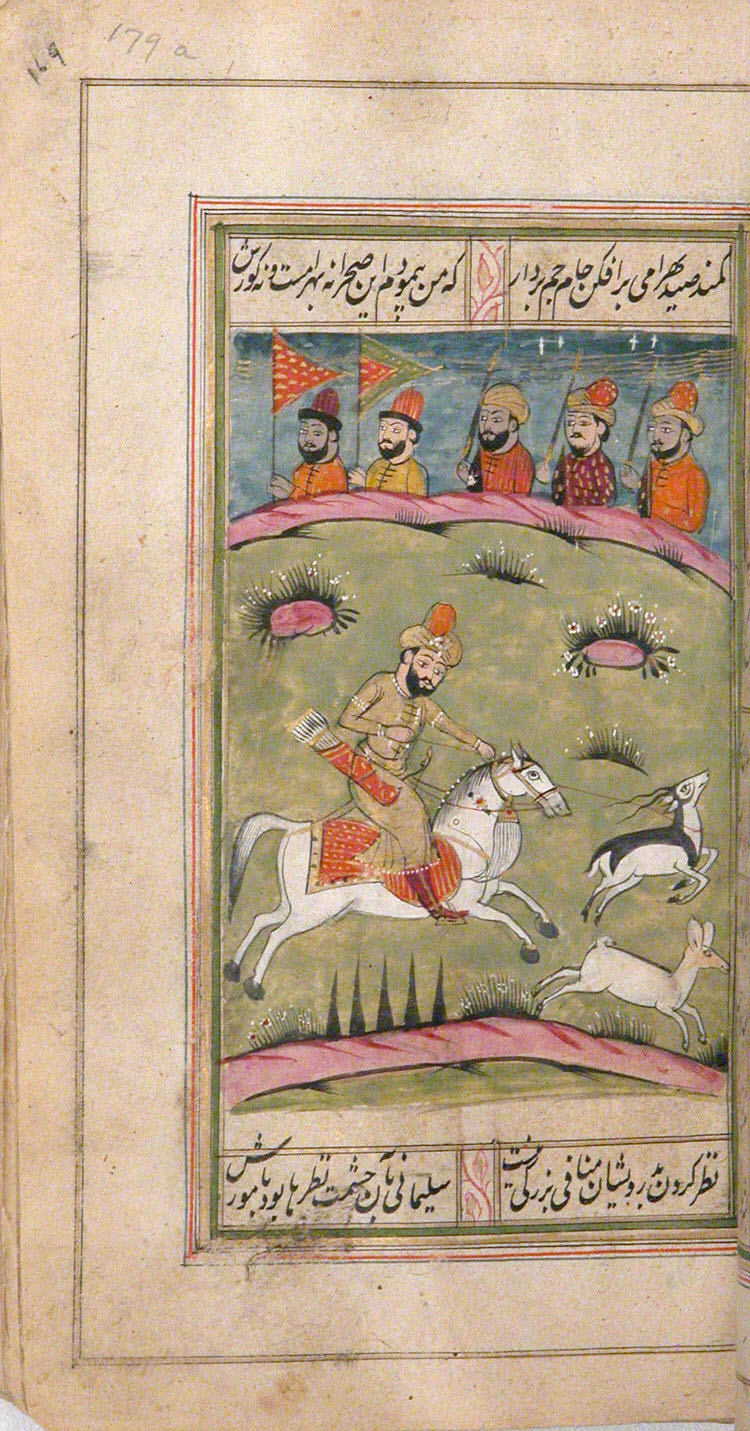

Translatability, Mysticism, and the Poetics of Untranslatability

As Babak Jabbari (2016) argues in his dissertation Persian Poetry in America: A Cultural Reception History, the reception of Persian poetry in American literature is marked by a tension between translatability and untranslatability. Its untranslatable aspects – linguistic density, cultural idioms, mystical references – become sites of creative reinvention, where American poets read Persian verse not only as text but as event, a catalyst for their own spiritual and aesthetic interrogations. Jabbari traces how Persian mysticism, especially in Rumi and Hafiz, entered American poetics as an experiential rather than purely philological mode, foregrounding the limitations and possibilities of translation as a form of literary hospitality.

Whitman, Stevens, and Quiet Echoes of Persian Structures

Later, Walt Whitman’s expansive embrace of the cosmos echoed Persian poetic structures of enumeration and inclusivity. Though not a direct inheritor of Persian forms, Whitman’s long lines and catalogues resonate with the aesthetic of abundance found in Sa’di’s Gulistan and Hafiz’s ghazals. Wallace Stevens’s philosophical abstractions similarly share an affinity with Rumi’s epistemic inversions and hermeneutics of paradox. Rumi’s radical metaphors – of turning, dying before death, and unveiling – find cognate expressions in Stevens’s poems of negation and becoming.

Rumi’s Resurgence in Late Twentieth-Century American Poetry

The influence of Persian poetry resurged powerfully in late twentieth-century American poetics, particularly through Jalal al-Din Rumi. His quatrains and ghazals entered the popular and literary imagination via translations and adaptations, most famously by Coleman Barks. However, as Omid Safi (2018) critiques, these reworkings often risk “spiritual consumerism” that decontextualises Rumi from his Islamic metaphysical and juridical commitments. Nonetheless, Rumi’s imagery of dissolution and divine intoxication entered the American lexicon of love and loss, reintroducing a poetics of ecstatic union at a time of cultural atomisation.

Jabbari (2016) further notes that the American reception of Rumi became a site where “mysticism was disembedded from its Islamic framework, reimagined as universal spirituality, and commodified for market audiences.” Yet, this same reception created avenues for deeper intercultural scholarship, fostering Persian language learning and comparative poetics in university curricula.

Orientalism, Empire, and the Ethics of Reception

The cultural and literary exchange between Persian and American poetry occurs within fraught histories of Orientalism, empire, and contemporary geopolitical violence. As Hamid Dabashi (2015) argues, Persian poetry circulates in the West within a paradox: its beauty is admired even as Persian-speaking peoples are targeted by war, sanctions, and racialisation. The rose of Hafiz becomes a tattoo, the quatrains of Rumi an Instagram caption, while Iranian civilians endure existential precarity.

Edward Said (1978) demonstrated how Orientalism constructs knowledge regimes that aestheticise the East while disavowing its political modernities. Jabbari (2016) expands this analysis by showing how Persian poetry’s “invisibility as literature” and “hypervisibility as spirituality” reflect and reproduce these structures. Thus, to read Persian poetry solely as an aesthetic object is to risk erasing its embodiment of survival, longing, and revolt.

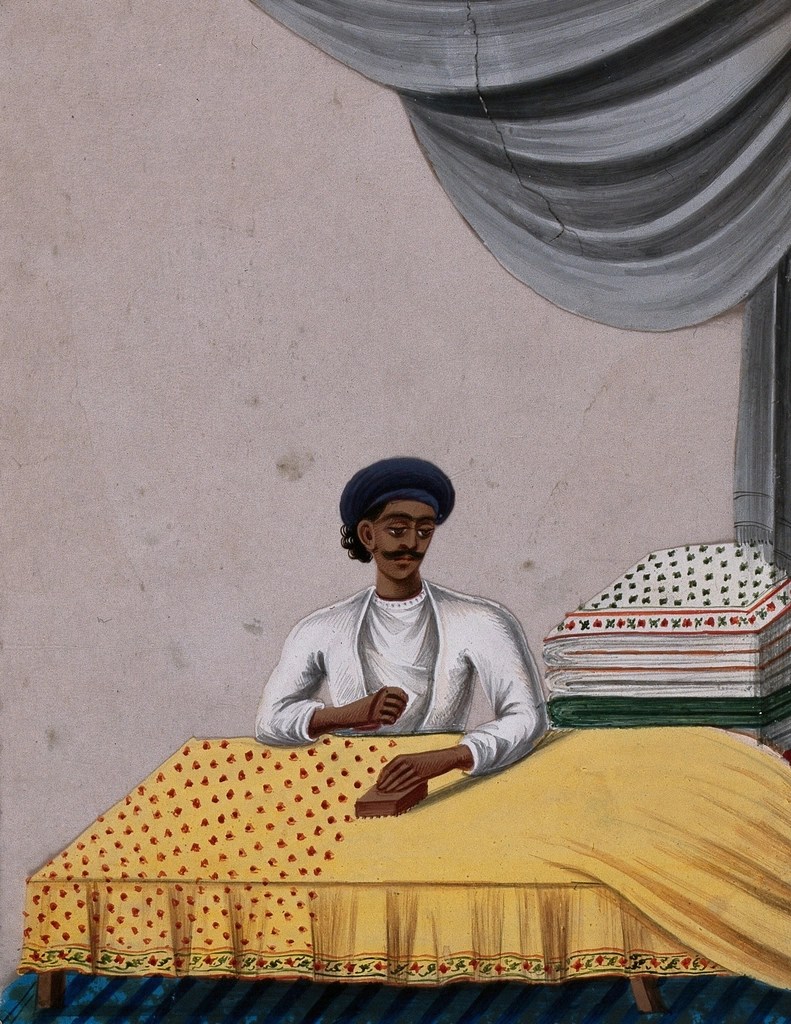

The Ghazal: Transnational Poetics Beyond Appropriation

The ghazal’s journey into American literature exemplifies a unique case of transnational poetics rather than straightforward appropriation. While Emerson’s engagement with Hafiz reveals the risks of aesthetic extraction – what Sedarat (2021) critiques as recontextualising Hafiz within a transcendentalist framework that erased his Islamic and Persian embeddedness – the ghazal’s later life in American poetry demonstrates a more complex and generative story.

Agha Shahid Ali, deeply rooted in Indo-Persian traditions, brought the ghazal into American English with fidelity to its radif, qafia, and maqta, insisting on its structural integrity while opening it to new thematic terrains. His line, “I see Kashmir from New York, one more / paradise lost in the journalistic sense” (Ali, 1997), enacts the ghazal’s capacity to hold grief, geography, exile, and political loss within its tightly patterned couplets. For Ali, the ghazal was not a borrowed form but a homeland of language, embodying what he called “real ghazals in English” (Ali, 2000).

Alongside Ali, poets such as Adrienne Rich adapted the ghazal deliberately as an instrument of feminist and political resistance. In Dark Fields of the Republic (1995), Rich reinterpreted the form’s discontinuities and imagistic leaps to rupture linear narrative and articulate dissent. The poets who followed in her footsteps often manhandled the form intentionally, bending its inherited constraints to express refusal and solidarity. In their hands, the ghazal became a vessel for transnational poetics: not an ornamental borrowing but an aesthetic strategy of radical re-visioning that resisted both English lyric conventions and Orientalist consumption.

Thus, while Emerson’s approach exemplified appropriation as aesthetic extraction, the ghazal’s later trajectory in American poetry stands as a testament to how poetic forms can cross languages and histories to become instruments of ethical encounter. Its adoption in American poetics remains a mirror, reflecting whether cultural borrowing becomes an act of consumption or a gesture of radical hospitality. In the works of Agha Shahid Ali, Adrienne Rich, and their successors, the ghazal enacts the possibility that form itself can become a vessel of solidarity, transformation, and resistance across borders.

Conclusion

Persian poetry remains urgent for American literature today. Its metaphors of exile (ghurbat), longing, and union gesture towards a relational aesthetics that does not merely consume the Other but acknowledges the ethical demand of their presence. The subterranean river of Persian influence continues to irrigate American poetry, reminding it of worlds beyond monolingual realism.

Epilogue: On Poetry, the Humanities, and Radical Hospitality

In an era of technological acceleration, rising authoritarianism, and market-based metrics that value only what is quantifiable, it is urgent to remember why poetry – and the humanities more broadly – matter. Persian poetry entered American literature not as a commodity but as an ethical and aesthetic force that asked new questions about love, mortality, justice, and beauty. It taught American poets to see the rose as both a flower and a veil, the beloved as both a body and a cosmic principle.

Research in literature and the humanities illuminates these complex entanglements of culture, power, and beauty. Without such scholarship, we risk reading only the surfaces of texts, stripping them of their histories of resistance, mysticism, and revolt. Without poetry, we risk forgetting the languages of longing that remind us of our fragile, shared humanity.

To support poetry is to support the possibility of a future in which language can still open a door into another’s grief and joy. To support the humanities is to defend the knowledge that we are more than data points and consumers; we are beings who dream, remember, and sing. In these darkening times, when war and border walls proliferate, poetry remains an act of radical hospitality. It is the rose offered to a stranger across a closed gate. It is the cry that traverses’ centuries to remind us that beauty and justice are never separable.

Footnote:

At the back of my mind are these two ideas: the concept of ziyafat – hospitality as sacred duty and radical welcome in Islamic tradition – and Derrida’s notion of hospitality, where true welcome is unconditional and risks unsettling the host. Both shape how I think about poetry, reading, and what it means to encounter the Other.

Ziyafat (Arabic: ضيافة) in Islamic tradition refers to hospitality as a sacred duty (fard kifayah) rooted in Qur’anic injunctions and prophetic practices. It involves honouring the guest with generosity, humility, and protection, and extends beyond kin to include travellers, strangers, and even enemies. The Prophet Muhammad said, “Whoever believes in God and the Last Day should honour his guest,” framing hospitality as an ethical and spiritual obligation (Sahih Bukhari 6018). In Sufi thought, ziyafat also embodies welcoming the divine guest – treating each visitor as a manifestation of God’s presence (cf. Chittick, Sufism: A Short Introduction, 2000). The approach and idea is closely related to Hindu culture as well, wherein similar threads can be found.

Jacques Derrida, in Of Hospitality (2000), develops the notion of radical hospitality by distinguishing between conditional hospitality (welcoming under certain terms or laws) and unconditional hospitality (welcoming the absolute stranger without preconditions). For Derrida, true hospitality risks destabilising the self or host; it is an ethical opening that exceeds legal, cultural, or economic calculation. In the context of transnational poetics, reading with radical hospitality means refusing to appropriate the Other’s text or form solely within one’s epistemic frameworks, instead allowing it to transform and unsettle the host culture’s aesthetic and political assumptions.

References

Ali, A. S. (1997). The Country Without a Post Office. W.W. Norton.

Ali, A. S. (2000). Ravishing DisUnities: Real Ghazals in English. Wesleyan University Press.

Dabashi, H. (2015). Persophilia: Persian Culture on the Global Scene. Harvard University Press.

Emerson, R. W. (1846). Translations from Hafiz. The Dial.

Jabbari, B. (2016). Persian Poetry in America: A Cultural Reception History. Boston University. https://open.bu.edu/handle/2144/14520

Keshavarz, F. (2012). Reading Mystical Lyric: The Case of Jalal al-Din Rumi. University of South Carolina Press.

Rich, A. (1995). Dark Fields of the Republic: Poems 1991-1995. W.W. Norton.

Safi, O. (2018). Radical Love: Teachings from the Islamic Mystical Tradition. Yale University Press.

Said, E. (1978). Orientalism. Pantheon Books.

Sedarat, P. (2021). Hafiz Translations and American Appropriations.

Leave a comment