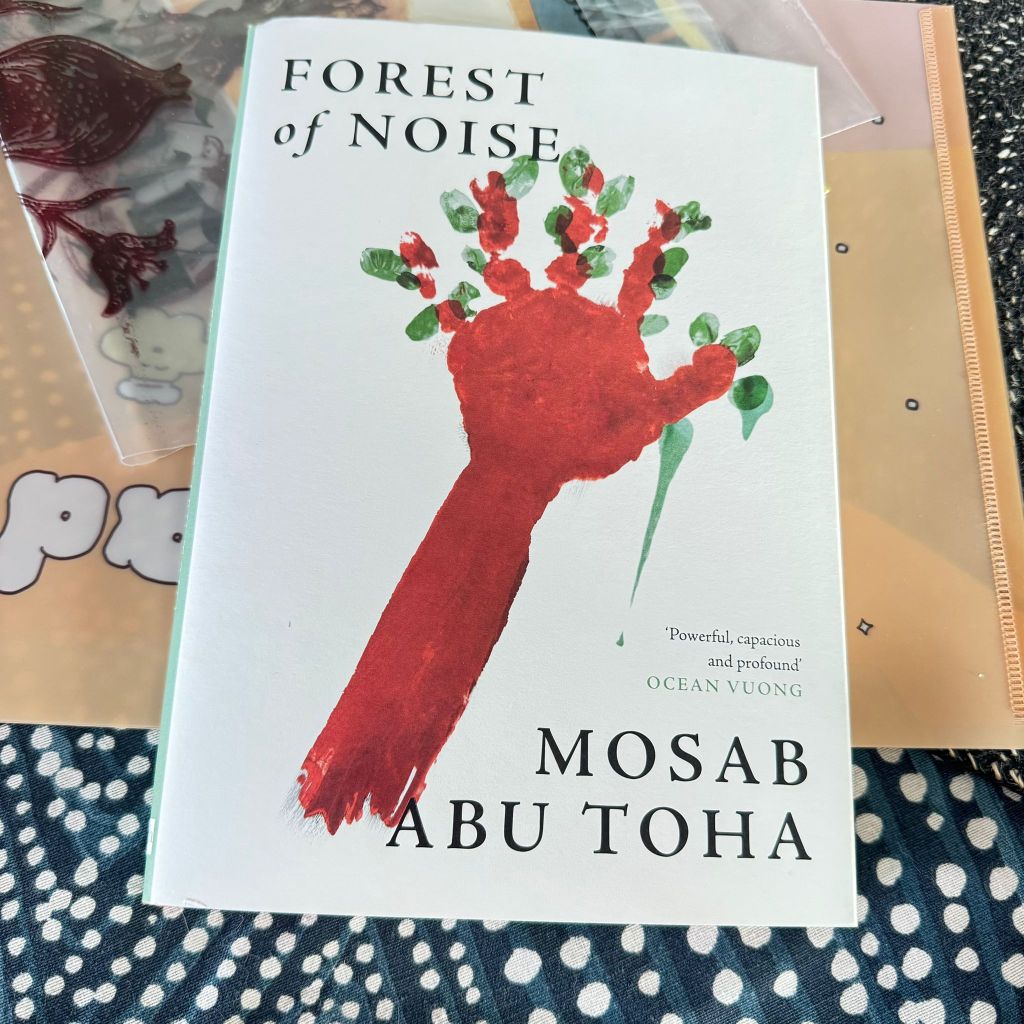

In Forest of Noise, Mosab Abu Toha offers us not just poetry, but the breathless residue of survival. The title itself rings like an invocation: a forest, dense with memory, static, and surveillance; a noise, unceasing, buzzing with drones, rubble, and the keening of the dispossessed. This is Gaza, yes—but also the poetic terrain of witness, rupture, and resistance. In this book, every tree is marked, every silence is suspect, and the noise—like history—refuses to be muffled.

Among the many shattering poems in the collection, “No Art” stands out as a fevered answer to Elizabeth Bishop’s poised villanelle, “One Art.” Bishop’s poem, with its refrain—“the art of losing isn’t hard to master”—offers a cool, almost ironic approach to personal loss. Abu Toha shreds that coolness, inscribing loss not as craft but as cataclysm. His response is urgent, trembling, and unsutured:

“I lose a city, / a cousin, / my sleep. / I lose the sentence halfway / when the airstrike begins.”

This is no longer metaphorical displacement; it is literal dismemberment. Where Bishop counts mislaid keys and forgotten names, Abu Toha inventories the losses of war, the absences that do not resolve into aesthetic distance. He resists the artifice of formality. “No art,” he writes, can master this.

The poem stages a refusal—not just of form, but of containment. And in doing so, Abu Toha aligns himself with a lineage of poets who have refused the anesthetic impulse of empire. The forest in Forest of Noise may well echo the impenetrable tangles of bureaucratic speech, drone surveillance, and international indifference. But it also evokes Walt Whitman’s forest of voices—his sprawling, ungovernable “Song of Myself,” where every blade of grass bears witness. Abu Toha’s catalogues, like Whitman’s, are lush with bodies, griefs, streets, textures of land. But unlike Whitman, he writes not from expansionist confidence but from siege. His is the song of a self that has watched the city burn and still chooses language.

The noise, too, is polysemic. It is the background hum of state violence. It is the disinformation of official reports. It is, crucially, the noise of the poet’s own beating heart. In the tradition of Allen Ginsberg’s Howl, Abu Toha howls not just for the “best minds” destroyed, but for the everyday minds—children, students, fathers, lovers—whose deaths are unarchived, whose lives are misnamed as “collateral.” Like Ginsberg, Abu Toha knows the power of repetition, of breathlessness, of breaking syntax to reach music. But his howl is shaped by a different geography, a different exile.

Visually and conceptually, Abu Toha also enters into dialogue with Brueghel’s Landscape with the Fall of Icarus, via Auden’s rendering of it in “Musée des Beaux Arts.” Just as Auden observed that the world “turns away” from disaster, so too does Abu Toha point to global complicity in Palestinian erasure. Icarus falls, legs flailing, barely noticed by the plowman or the ship. Gaza is shelled, and the world scrolls past. The poet, however, does not turn away. He writes. He listens to the fall.

In her essay When We Dead Awaken: Writing as Re-Vision, Adrienne Rich declared that for women—and, we might add, for the colonized—”re-vision” is not a luxury, but a survival tactic. Abu Toha’s revision of Bishop is not merely poetic; it is political. It is the act of reclaiming voice from the ruins. This is the territory where the personal is political, and where the political is perilously personal. There is no safe remove.

And so Forest of Noise becomes not only a poetic collection, but a terrain of refusal. Audre Lorde’s words echo here: “Poetry is not a luxury. It is a vital necessity of our existence.” In a land where writing can be interrupted by an airstrike mid-sentence, poetry is not an adornment. It is an act of defiance. A continuation of life by other means.

Why is Abu Toha’s poetry so fevered? Because it must be. In Gaza, fever is both a symptom and a signal. It is the body’s way of resisting infection. Likewise, poetry here burns not to illuminate, but to survive, to cauterize the open wound. The fire is political, but it is also deeply poetic. In a world trained to turn away, Abu Toha’s voice refuses decorum, refuses forgetfulness. His is a poetry that makes you stay. Makes you hear.

Because beneath the noise, in the deepest roots of this forest, there is a clarity: the human insistence to name, to sing, to remember.

Citations:

- Abu Toha, Mosab. Forest of Noise. 4th Estate, 2024.

- Bishop, Elizabeth. “One Art.” The Complete Poems: 1927–1979, Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 1983.

- Rich, Adrienne. “When We Dead Awaken: Writing as Re-Vision.” On Lies, Secrets, and Silence, Norton, 1979.

- Rich, Adrienne. Of Woman Born: Motherhood as Experience and Institution. Norton, 1976.

- Lorde, Audre. “Poetry Is Not a Luxury.” Sister Outsider: Essays and Speeches, Crossing Press, 1984.

- Ginsberg, Allen. Howl and Other Poems. City Lights Books, 1956.

- Auden, W.H. “Musée des Beaux Arts.” Collected Poems, Faber & Faber, 1976.

Leave a comment